This was a piece of childhood recollection I wrote back in 2020. I’ve self-published it as a zine for Big Chicken & Baby Bird’s previous show “Step into the Water and You Remember Everything” before (you can find that zine in my store and the proceeds is split between Nat an I). I recently submitted this piece of writing as an entry for Canto Cutie, a zine for Cantonese diaspora, which I am also one of the editors for. I have also posted it here on Instagram before, but I figured some of you who are new to following me haven’t seen it. So here we go.

When I was a child, I lived in a small public housing unit with my grandparents and my uncle in the Wong Tai Sin district in Hong Kong. I shared a room with my grandmother and my uncle. My uncle slept on the upper bunk and I slept on the lower bunk with my grandmother. My grandfather smoked incessantly, so no one wanted to share a room with him. There were a lot of things in our bedroom, plastic bags stacked on top of plastic boxes. There was a window behind it all, I might have climbed up the mountain of stuff to look out of it a few times. The view was just the residential building opposite ours. The buildings were white and pastel orange and they were all the same. I imagine the people from the other side got the same view when they looked out of their windows.

We had more stuff than what we stacked against the window. We also had other things stored temporarily on our beds during daytime. My uncle had an impressive collection of vintage toys and comic books, most of it were these really well designed vintage matchbox cars made in Japan by the famous toymaker Tomy and the various McDonald’s Happy Meal toys from the Hong Kong line throughout the years. Grandma just had a bunch of clothing from when both of her oldest daughters immigrated to America. They were going to be my hand-me-downs when I fit, or so she told everyone. Every night around ten, we’d start moving the boxes from our bunk beds to the dining table. After taking a hot shower and washing off the grime that stuck to my skin due to the humid weather, I’d climb onto the lower bunk. If my uncle didn’t have too much work (his actual work plus coming up with the perfect combo for his weekend horse betting), he’d read me a bedtime story. He bought me a collection of illustrated Aesop’s Fables and other animal stories that he’d read from. When grandma was done with her chores in the kitchen, she’d come to bed and pat me as she sang me lullabies.

I slept between the wall and my grandma. There was no space between the wall and the bed because the bed was custom built in by my second aunt’s husband, who is an interior designer and carpenter. The wall was cool, offering relief from the oppressive heat in the long, humid summer. I’d often stretch my leg up against the wall to absorb the chill. During the summer, instead of cotton sheets, we slept on bamboo mats. When I woke up, I’d find ghosts of the crisscross imprints on my skin from the bamboo weave.

Sometimes I’d wake in the middle of the night for the bathroom. I’d usually stay in bed for a good while, struggling between the need to pee and not wanting to get up. You see, the pile against the window made strange figures and silhouettes in the dark, sometimes flickers of light reflected from somewhere looked like an eye, or I’d imagine a face, or a pile that began to look like a figure moving. When I really couldn’t suppress my need to pee, I’d climb over my grandma, careful not to wake her, and put my warm little feet upon the icy ceramic tile. If it’s around 1:30 AM, I’d find a tall, slender silhouette walking to the bathroom too. It was my grandfather getting out of his room to shower before bed. Grandpa went to bed the latest and woke up later than all of us. I think it’s because all his favorite shows from the English channel came on late, and he had to watch it all before he went to sleep. I didn’t particularly like the living room at night because we had an altar. The altar was lit by a few red light bulbs, which made the dark living room quite ominous. The altar also directly faced the front door, which made it look like something was about to come through under this low, red glow. If I wanted to use the bathroom, I had to walk right past the altar. My grandma always told me the altar was good, we venerated our ancestors, the god of land, and the god of justice; they were there to watch over us and give us good fortune. Every time I walked past the bathroom at night, I’d mutter under my breath a small “唔該借歪” / “excuse me”. I didn’t want to offend these important figures with my nightly urination. If I was too scared after peeing to make the trip back to my spot between the wall and my grandma, I’d quickly run into my grandpa’s room and watch TV with him until I felt brave enough to go into the living room again.

——

For the most recent volume of Canto Cutie, I came across another artist’s submission that was a photography project about how they struggled with how her relatives in Hong Kong view her tattoos. I wrote this to accompany the previous writing as a response:

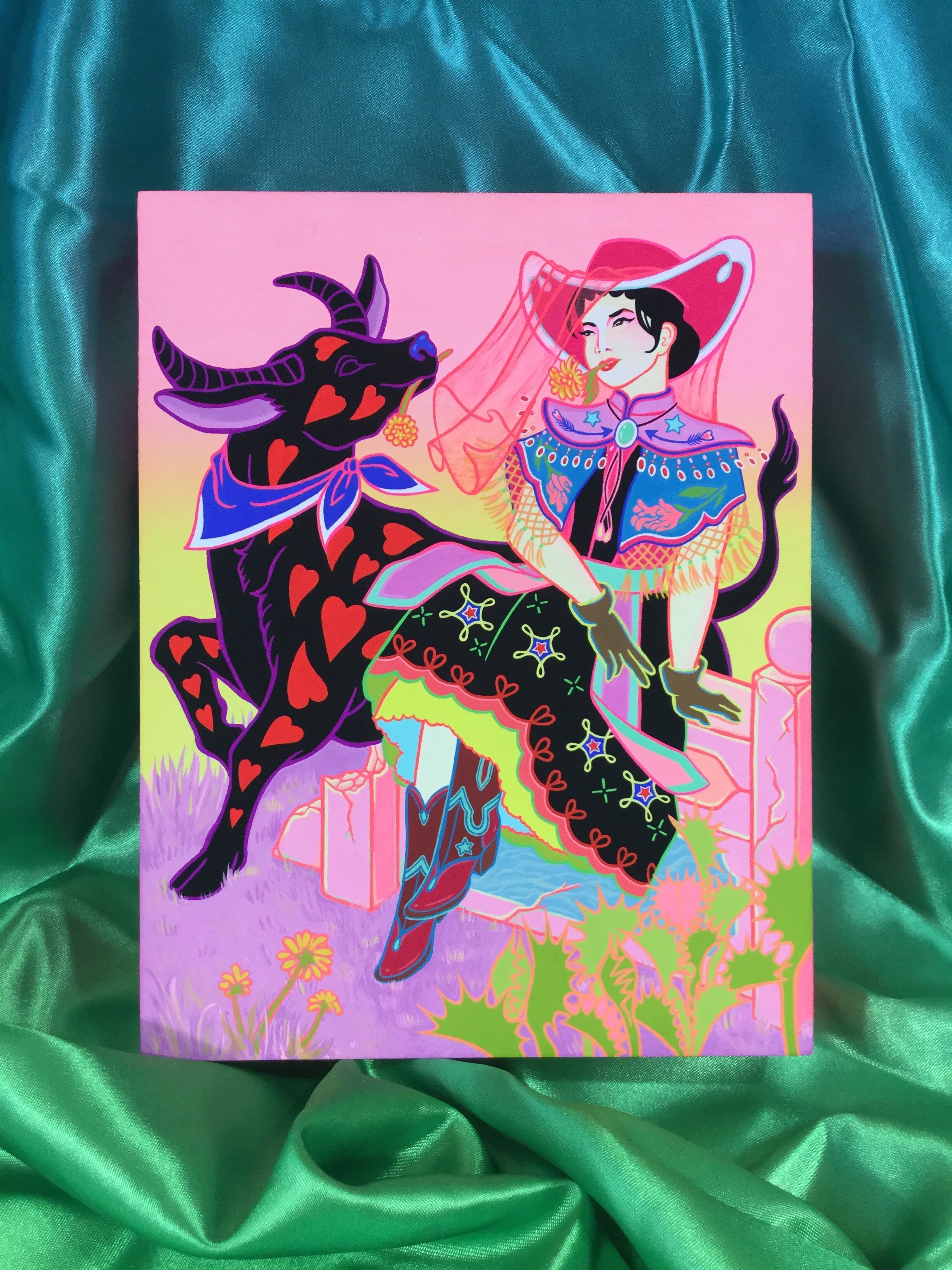

This was a recollection I wrote in early 2020 for my painting “Silent Witness’s Triumph”. The painting depicts two beastial entities as one single grotesque figure. One entity is a pegasus and the other is some kind of bovine. I took inspiration from the Chinese mythology about how seven days after someone’s death, Ox-Head and Horse-Face will escort their spirit home for one last meal prepared by their family. Ox-Head and Horse-Face always come in a pair, and are seen as agents of the underworld in Chinese folk religion, a very popular belief system that still permeates Hong Kong culture. Silent Witness was the name of a thoroughbred champion sprinter in the Hong Kong Jockey Club. Early in its career in 2003, many HKers were very proud of this race horse’s international fame, and seeing Silent Witness win at international races brought much joy to HKers during the post 2003 SARS pandemic period. Horse betting, just like any other other gambling activities in Hong Kong, is also shrouded in superstition. I believe that we thought after such a period of bad luck with the pandemic, Silent Witness represented hope as a cultural icon.

The painting, Silent Witness’s Triumph. It was part of the exhibition Step into the Water and You Remember Everything at Clamplight in San Antonio in 2020.

Stories of superstitious myths scared me as a child but I also had a sort of fascination and unquestioned reverence for the figures in these myths, an attitude that continues in my adulthood. Even though I have moved to Texas for over a decade, these superstitions still have some small power over me and the way I think. Since early 2020, I’ve become more and more interested in the grotesque and monsters as art subjects in my personal work. My long time friend and artistic collaborator, Nat Power (@natpowertat), began her apprenticeship as a tattoo artist in 2019 and has since then been sharing her various knowledge about tattooing with me. Although I’ve never been interested in getting tattoos and still am not, I’ve begun to expand my appreciation for tattoos as art. Before the Covid pandemic, I used to visit Nat at the tattoo parlor she worked at and spent time with her there, sometimes listening in on Ray, Nat’s mentor, coaching her on drawing methods. Ray (@flawless.wallace.tattoos) is the owner of the tattoo parlor and a tattoo artist of Indonesian descent. Nat and her mentor shared with me the history of tattooing in different indigenous cultures around the world. One time Ray even showed me a dice game tattoo artists often played amongst themselves, and told me the game was probably brought to America by Chinese sailors in the 1800s. After learning this, I started doing some research on my own and discovered that tattooing was also a cultural practice by the Baiyue peoples, the group of peoples who some Cantonese and Vietnamese people are originally descended from before they were sinocized by the Han. As a person with a pretty traditional Hong Kong upbringing, I still don’t feel the urge to get tattoos myself, but I have begun to incorporate some of the observations I’ve made about tattoo graphics into my own personal paintings.

Growing up in Hong Kong society, I was often told that only triad members sported tattoos. This is why HKers have such prejudice against people who have visible tattoos; people with tattoos were supposed to be unsavory people affiliated with gang activities. Today, attitudes about tattoos have changed in Hong Kong as more and more young people just think of it as a personal choice. Personally though, I still appreciate the original intention with which triad tattooing was performed— people who acquired triad tattoos sometimes did it because they believe having a mythical beast or entity tattooed allows them to channel the power of that entity. I have also heard supernatural anecdotes about people getting mysteriously sick after getting a tattoo of a powerful entity, presumably because they were not spiritually “strong enough” to control the entity’s power.

As a queer artist, Nat speaks of her tattoo practice as collecting animal icons as sentimental figures, almost adjacent to the modern-day Internet furry subculture that celebrates things like fursona and adoptables, practices where young queer kids project themselves and their identities onto self-invented or peer-invented animal characters. This inspired me to follow my instincts. I’ve always been interested in monsters and mythological figures. I didn’t have a concrete reason to justify why I wanted to draw and paint them before; I am just never one to draw or paint something simply because “I like it”. I need to know why and where it comes from. It’s taken a long way from Wong Tai Sin to Texas to find it, but I have found it.

After discovering Puca’s photography project about Wong Tai Sin, my childhood home, and her struggle with how her relatives in Hong Kong see her tattoos, I wanted to share these thoughts with the community. This is a love letter about how a kid from Wong Tai Sin fell in love with tattoo art, even though they still won’t get a tattoo themself.